What’s included

- Multi-Agent RL for Adaptive UIs

- Is ‘Programming by Example’ (PBE) solved by LLM’s

- Learning Iterative Reasoning through Energy Diffusion

- LORA: Low-Rank Adaptation of LLMs

- Automating the Enterprise with Foundational Models

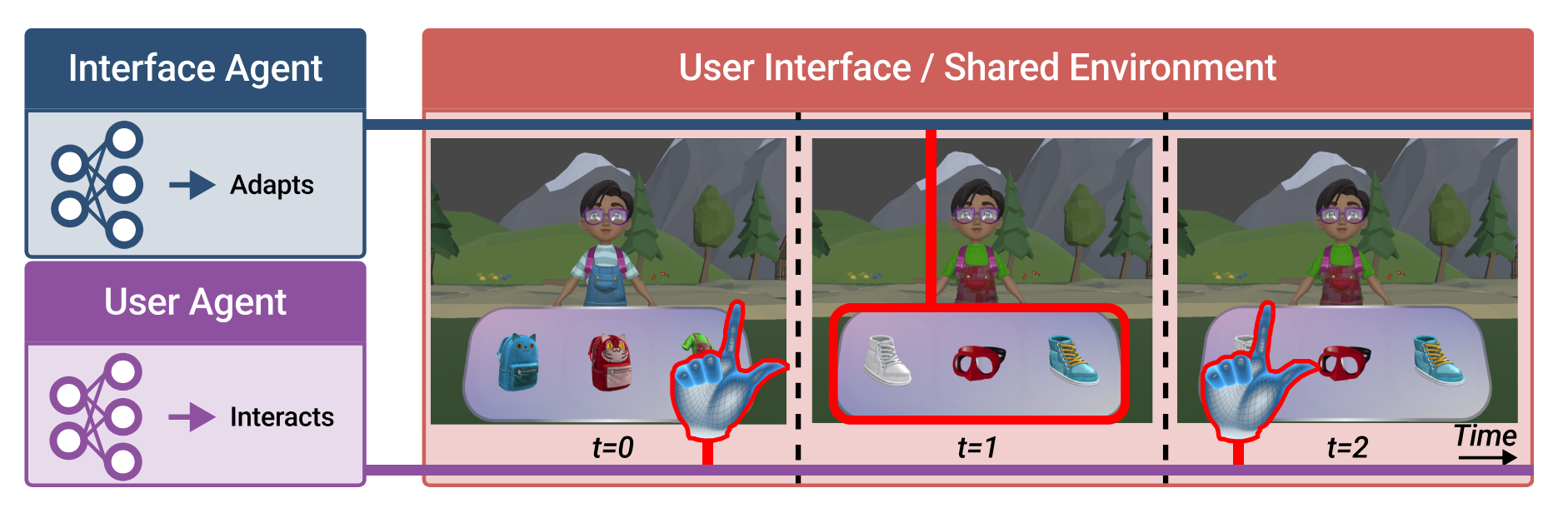

MARLUI - Multi-Agent RL for Adaptive UI

ACM Link: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3661147 Paper: MARLUI

Adaptive UIs

Adaptive UIs - as opposed to regular UI’s, are UI’s that can actually adapt to the users needs. In this paper, the UI is adapting to optimize the number of clicks needed to reach the outcome. The paper uses an RL schema, to automatically learn a policy that can be applied for UI optimizations. I like the fact that this removes the need to collect massive amounts of user-data, and subsequent data analysis to understand the patterns and manually optimize for them via heuristics / training specific models.

2-Agent method

At its core, the paper tries find a RL mechanism for training two agents.

User-Agent: Given a goal, point and clicks on the UI to achieve the goal. In the paper, the goal is to dress a character by choosing elements from a toolbar.

Interface-Agent: A collaborative agent, that aims to modify the UI such that it allows the agent to achieve the optimization goal.

At its core, the paper tries find a RL mechanism for training two agents.

User-Agent: Given a goal, point and clicks on the UI to achieve the goal. In the paper, the goal is to dress a character by choosing elements from a toolbar.

Interface-Agent: A collaborative agent, that aims to modify the UI such that it allows the agent to achieve the optimization goal.

From the paper

Adaptive User Interfaces (AUIs) seek to mitigate this complexity by dynamically adjusting the interface presented to the user to display the items that are most relevant to the user’s current task, while omitting less relevant information. This simplifies visual information processing and eliminates the user’s need for navigating through complex interfaces such as hierarchical menus that require multiple actions to eventually select one item.

Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDP)

is a mathematical framework for singleagent decision-making in stochastic partially observable environments [2], which is a generalization over Markov Decision Processes [45]. A POMDP is a seven-tuple (𝑆,𝑂, 𝐴,𝑇 , 𝐹, 𝑅,𝛾), where 𝑆 is a set of states, 𝑂 is set of observations and 𝐴 is a set of actions.

Multi-Agent RL

A partially observable stochastic game is defined as an eight-tuple (𝑁 , S, O, A,𝑇 , F, R,𝛾), where 𝑁 is the number of policies. S = 𝑆1 × … ×𝑆𝑁 is a finite set of state sets, and O = 𝑂1 × … ×𝑂𝑁 is a finite set of observation sets, with subscripts indicating different policies. A = 𝐴1 × … × 𝐴𝑁 is a finite set of action sets. 𝑇 is the transition probability function. F = 𝐹1 × … × 𝐹𝑁 defines a set of observation probability functions of different players. A set of reward functions is defined as R = 𝑅1, …𝑅𝑁 . Furthermore, we define a set of policies as Π = 𝜋1, …𝜋𝑁 . Finally, 𝛾 is the discount factor. All policies have their individual actions, states, observations, and rewards. In this paper, we optimize each policy individually, while the observations are influenced by each other’s actions. We use model-free RL

Modelling the user-agent?

We model the user agent as a hierarchical agent with separate policies for a two-level hierarchy [61]. First, we introduce a high-level decision-making policy 𝜋𝑑 that computes a target for the agent (high-level decisionmaking), we approximate visual cost with the help of existing literature [20]. Second, a WHo Model Fitts’-Law-based low-level motor policy 𝜋𝑚 that decides on a strategy

Procedure for testing

Participants interacted with the interface agent and the two baselines. The three settings were counterbalanced with a Latin square design, and the participants completed 30 trials per setting. In each condition, we discarded the first six trials for training. The participants were instructed to solve the task as fast as possible while reducing the number of redundant actions. They were allowed to rest in-between trials

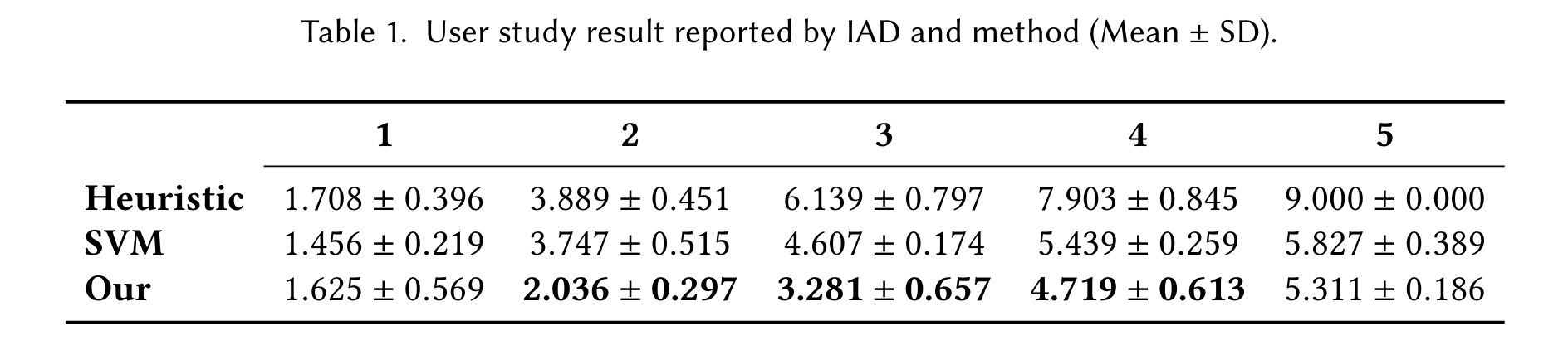

Results

We present a summary of our results in Figure 7. We analyzed the effect of conditions on the performance of participants with respect to the number of actions and task completion time. Participants needed on average 3.34 actions to complete a task with our framework, compared to 5.73, and 3.87 for the static, and SVM baselines respectively.

Is Programming by Example solved by LLMs?

Paper: PBE-by-LLM

What is Programming-by-Example

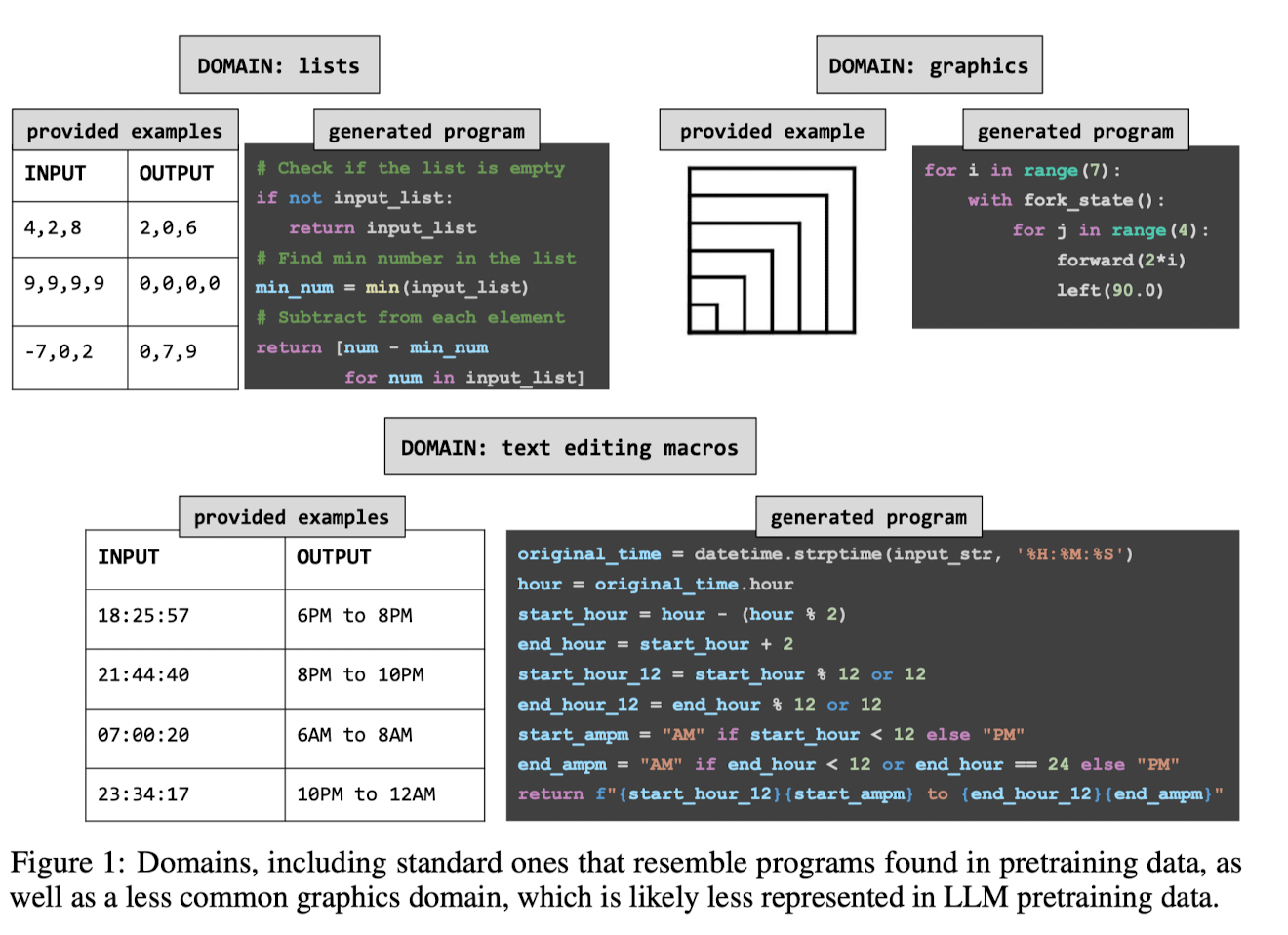

Programming-by-Examples (PBE) aims to generate an algorithm from input-output examples. There is no natural language instruction here, but simply the input-ouput tuples to synthesize a program that matches the input/output pairs.

PBE corresponds to a very general form of few-shot inductive inference, so LLM’s are natural choice for this.

In summary: Given input-output examples of a hidden algorithm, they seek to construct the source code of the underlying function

The punch line

We find that pre-trained and instruction-tuned models serve as poor PBE systems, a finding also supported by recent work [15, 12]. But our investigation further finds that LLMs can be fine-tuned for significantly higher performance, provided they are not asked to generalize far beyond the fine-tuning data. To address this failure of generalization we give an algorithm for taking a small unlabeled dataset of problems and adapting the LLM to it, which we find narrows this domain gap.

From the paper

the PBE system FlashFill synthesizes string manipulation macros designed to automate common spreadsheet edits [2]. FlashFill’s domainspecific language L includes commonly occurring regular expressions, together with string slicing and concatenation, and restricted forms of loops. TIL: Excel uses a PBE Fine-tuning improves the above approach in a conceptually straightforward way. Given a dataset comprising tuples of programs and I/O examples, {(ρ, X, Y)}, we fine-tune the LM to predict a program from its input-outputs. But this dataset is hard to come by: Although there are web-scale corpora of naturally occurring source code, there is no analogous dataset of runnable code snippets paired with representative input-output examples, and this data deficit is especially true for new or unusual applications of PBE, such as the graphics programs we consider.

How they generate the data to fine-tune

To assemble a large dataset of (ρ, X, Y) triples we start with a small manually-constructed seed dataset, Dseed, and then randomly generate new programs ρ and inputs X by prompting an LLM with members of Dseed. The output Y comes from running ρ on X.

Results

The resulting fine-tuned models are surprisingly effective within their respective PBE domains. On list functions our finetuned model surpasses the best symbolic search baselines reported in Rule et al. (Fig. 3a), surpasses the best neurosymbolic search method from Shi et al. (Appendix Fig. 10), and surpasses GPT4.

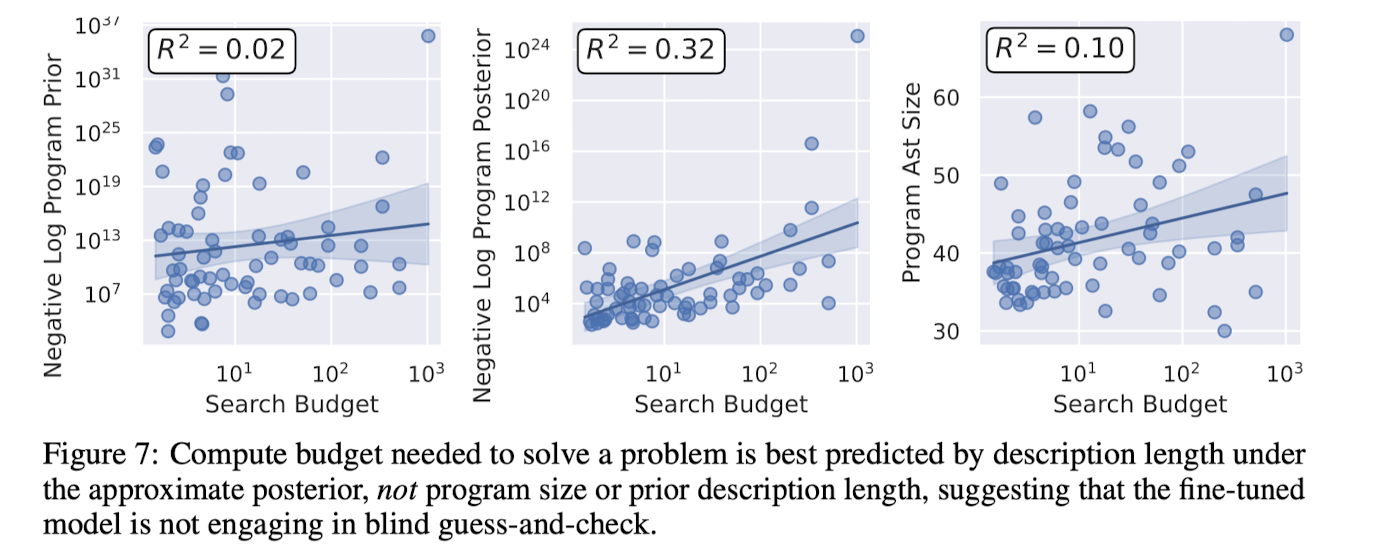

Interesting evaluation of hypothesis

1. Relation to program-size. Does it degrade, for longer programs?

2. Description length under prior - Is the model guess-and-checking from learned distribution and sampling from it

To test these hypotheses we calculate the average compute budget needed to solve each problem, and compare it with these different variables. Fig. 7 shows that posterior description length is more predictive than program size and prior description length >

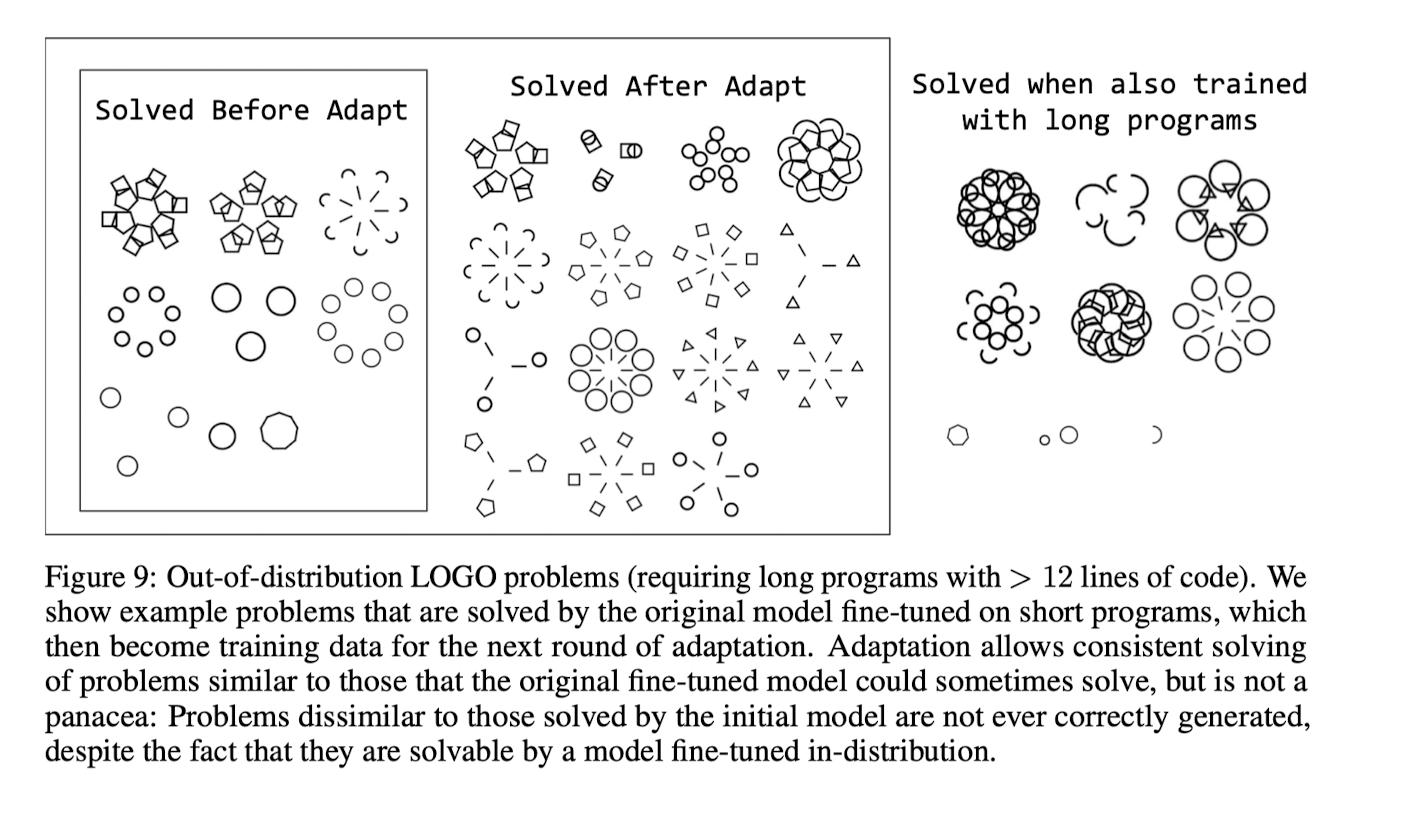

Out-of-distribution generalisation

Before adaptation, only a handful of out-of-distribution problems are solvable, and only with a significant search budget. Adaptation allows the system to quickly solve similar out-of-distribution problems in the future, but does not allow the system to generalize to problems very unlike those originally solvable by the fine-tuned model.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, the neural network only needs to act as a heuristic proposer of solutions, because we can check against the input-outputs. Therefore, one possible explanation is that the tendency of language models to over-generate, hallucinate, and cover the long tail of possibilities is actually an asset, instead of a liability. And although there is a degree of degradation on out-of-sample problems, the degradation is not so severe that out-of-distribution problems become utterly unsolvable: Instead, they merely become harder to solve, a phenomenon that allows adaptation to work in the first place.

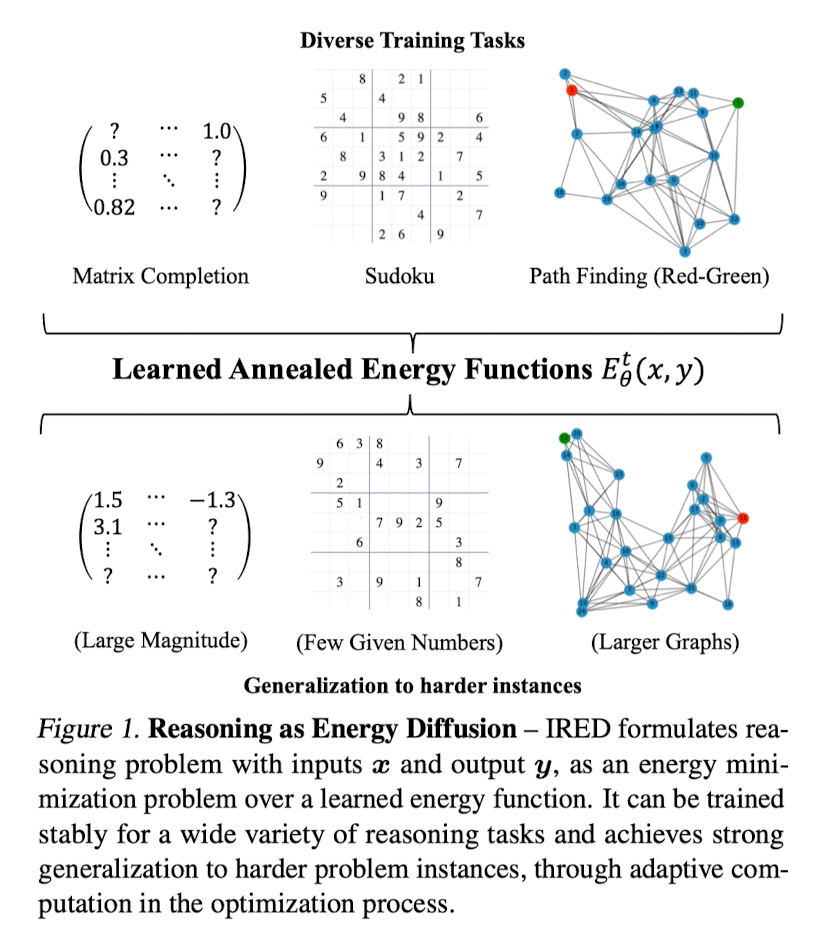

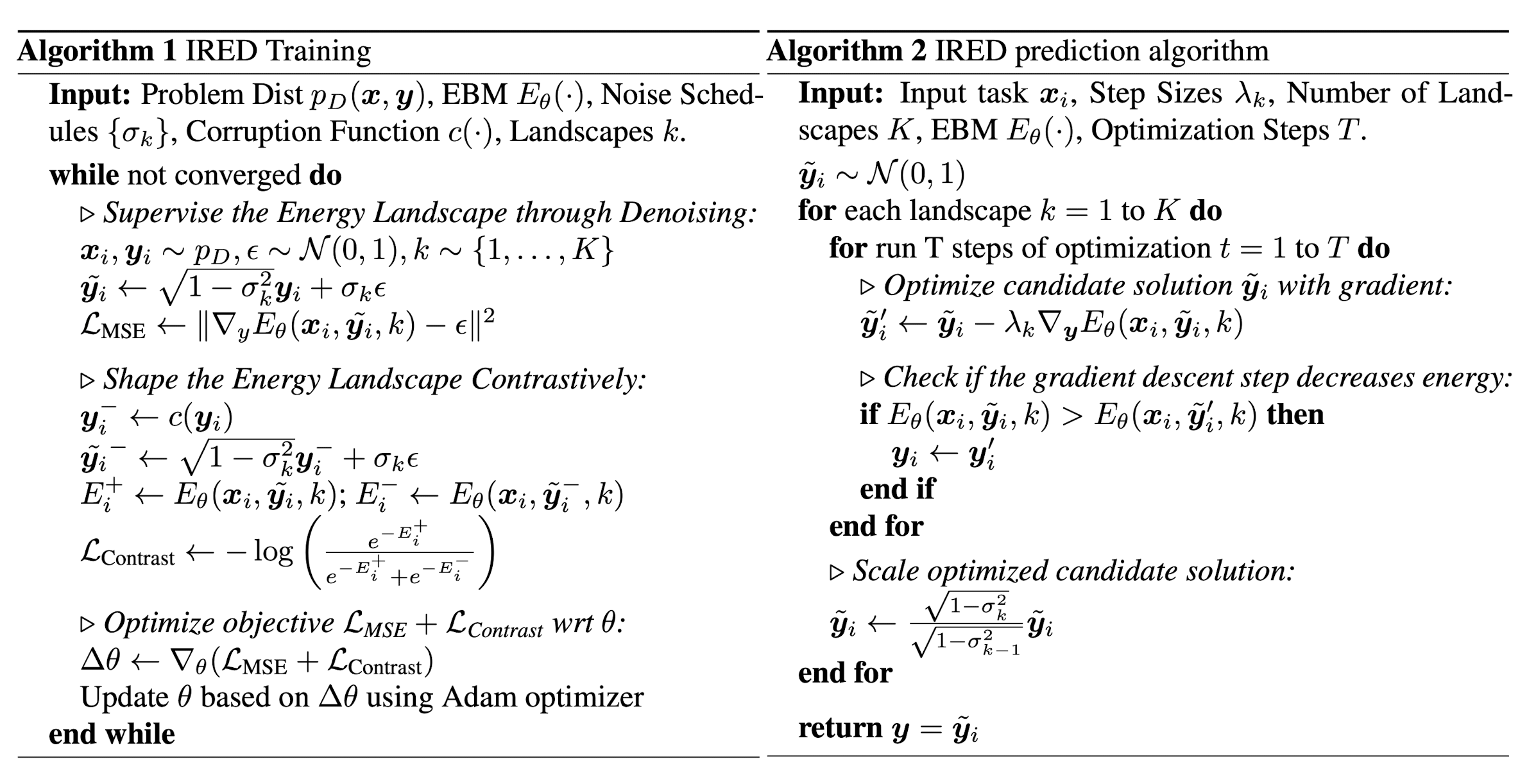

Learning Iterative Reasoning through Energy Diffusion

Punch Line

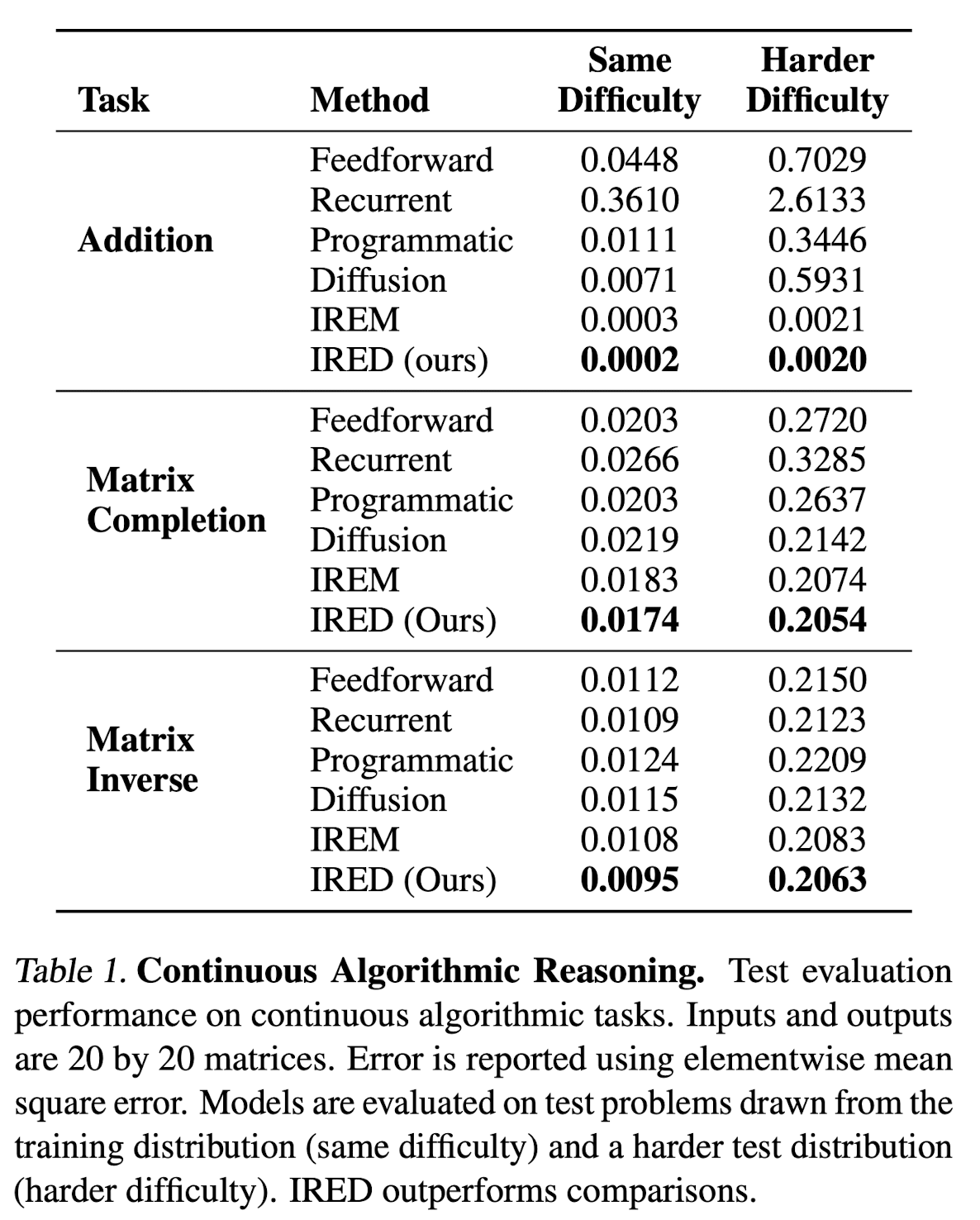

IRED learns energy functions to represent the constraints between input conditions and desired outputs. After training, IRED adapts the number of optimization steps during inference based on problem difficulty, enabling it to solve problems outside its training distribution — such as more complex Sudoku puzzles, matrix completion with large value magnitudes, and path finding in larger graphs. Key to our method’s success is two novel techniques: learning a sequence of annealed energy landscapes for easier inference and a combination of score function and energy landscape supervision for faster and more stable training. Our experiments show that IRED outperforms existing methods in continuous-space reasoning, discrete-space reasoning, and planning tasks, particularly in more challenging scenarios.

What are ‘Energy Functions’ ?

For example: logical deduction can be cast as finding possible assignments to variables that satisfy all logical constraints; theorem proving can be cast as finding a sequence of valid deduction steps that entails the goal; planning can be cast as finding a sequence of actions that respect the transition model of the environment and achieve the goal. I found an interesting illustration of energy functions in an old Open AI post : https://openai.com/index/learning-concepts-with-energy-functions/ >

Many hallmarks of human intelligence, such as generalizing from limited experience, abstract reasoning and planning, analogical reasoning, creative problem solving, and capacity for language require the ability to consolidate experience into concepts, which act as basic building blocks of understanding and reasoning. Our technique enables agents to learn and extract concepts from tasks, then use these concepts to solve other tasks in various domains. For example, our model can use concepts learned in a two-dimensional particle environment to let it carry out the same task on a three-dimensional physics-based robotic environment—without retraining in the new environment.

Model setup

Let D = {X, Y} be a dataset for a reasoning task consisting of inputs x ∈ R O and corresponding solutions y ∈ RM. We aim to learn a neural network-based prediction model NNθ(·) which can generalize execution NNθ(x ′) to a test distribution x ′ ∈ R O′, where x ′ can be significantly larger and more challenging than the training data x ∈ X (e.g., of higher dimensions, or with larger number magnitudes), by leveraging a possibly increased computational budget.

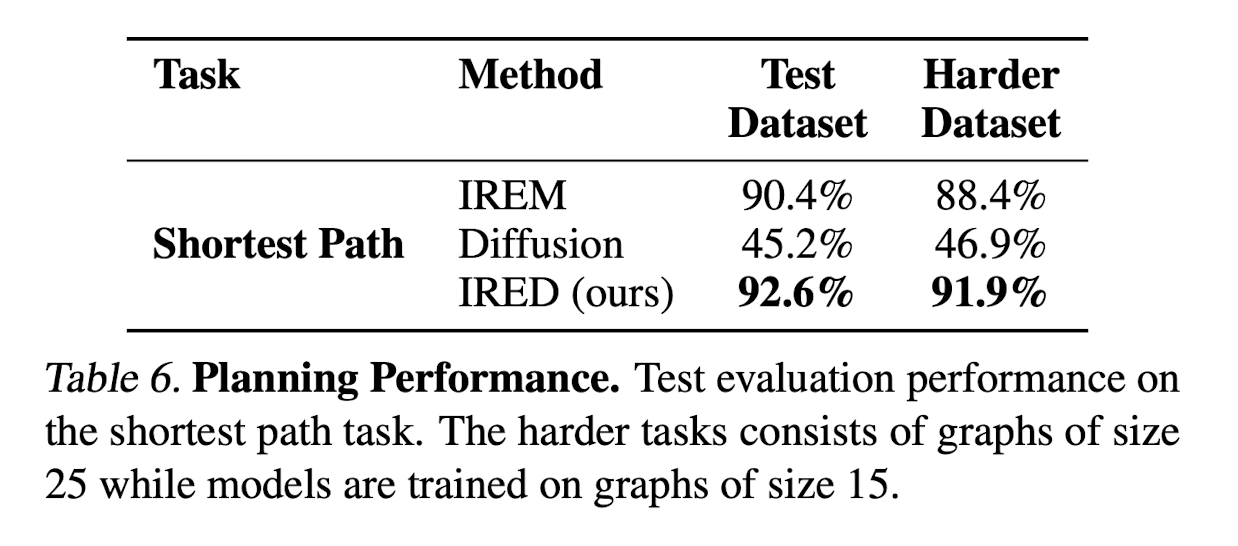

Results

Continuos Algorithm Reasoning

Planning

In this section, we evaluate IRED on a basic decision-making problem of finding the shortest path in a graph. In this task, the input to the model is the adjacency matrix of a directed graph, together with two additional node embeddings indicating the start and the goal node of the path-finding problem. The task is to predict a sequence of actions corresponding to the plan.

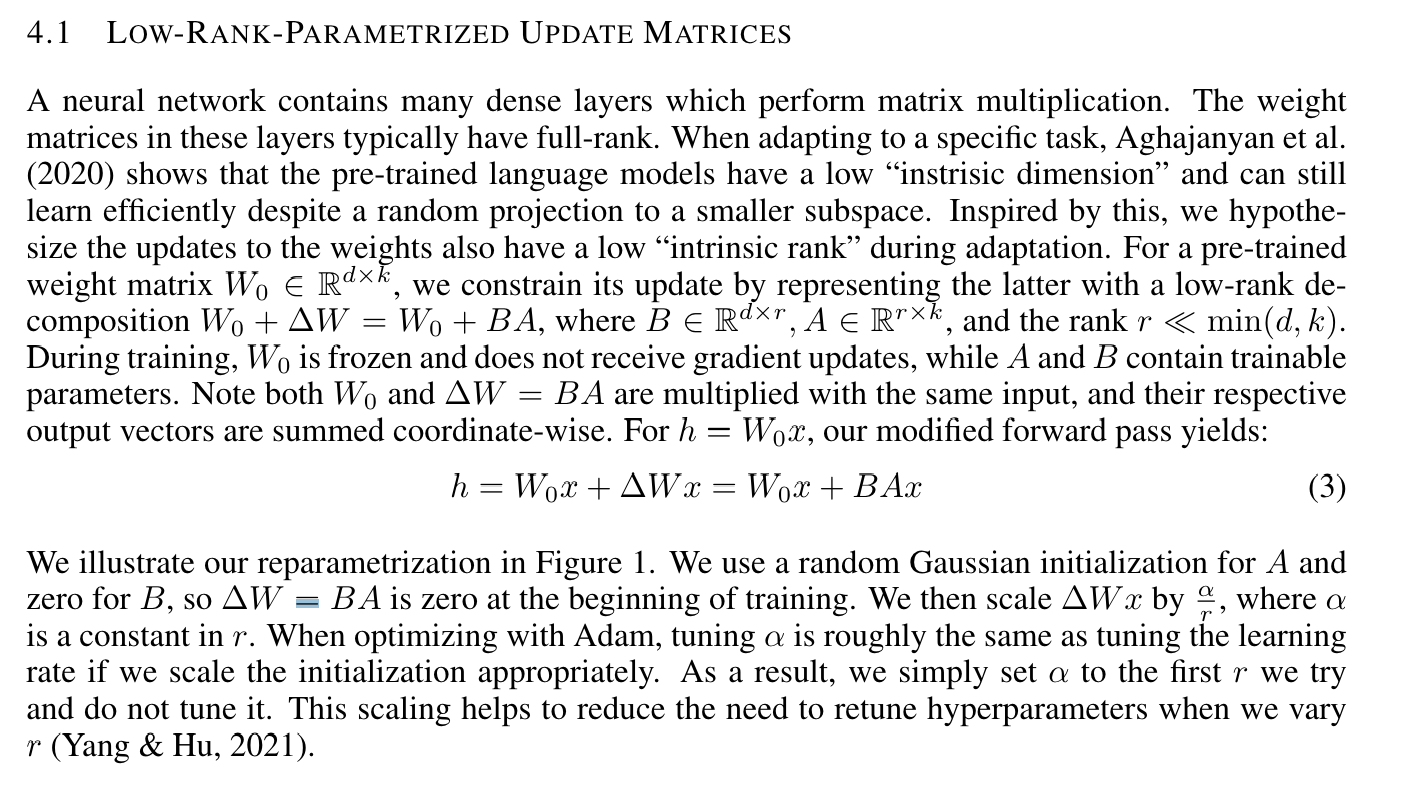

LORA - Fine-tuning LLMS

Paper: LORA Honestly - this paper is so seminal for fine-tuning methods, that I think you should really read it, instead of reading this summary. But here’s the summary for the mathematically less-inclined / just want to know what it roughly does.

LoRA allows us to train some dense layers in a neural network indirectly by optimizing rank decomposition matrices of the dense layers’ change during adaptation instead, while keeping the pre-trained weights frozen LoRA possesses several key advantages. • A pre-trained model can be shared and used to build many small LoRA modules for different tasks. We can freeze the shared model and efficiently switch tasks by replacing the matrices A and B in Figure 1, reducing the storage requirement and task-switching overhead significantly. • LoRA makes training more efficient and lowers the hardware barrier to entry by up to 3 times when using adaptive optimizers since we do not need to calculate the gradients or maintain the optimizer states for most parameters. Instead, we only optimize the injected, much smaller low-rank matrices. • Our simple linear design allows us to merge the trainable matrices with the frozen weights when deployed, introducing no inference latency compared to a fully fine-tuned model, by construction. • LoRA is orthogonal to many prior methods and can be combined with many of them, such as prefix-tuning. We provide an example in Appendix E. The crux

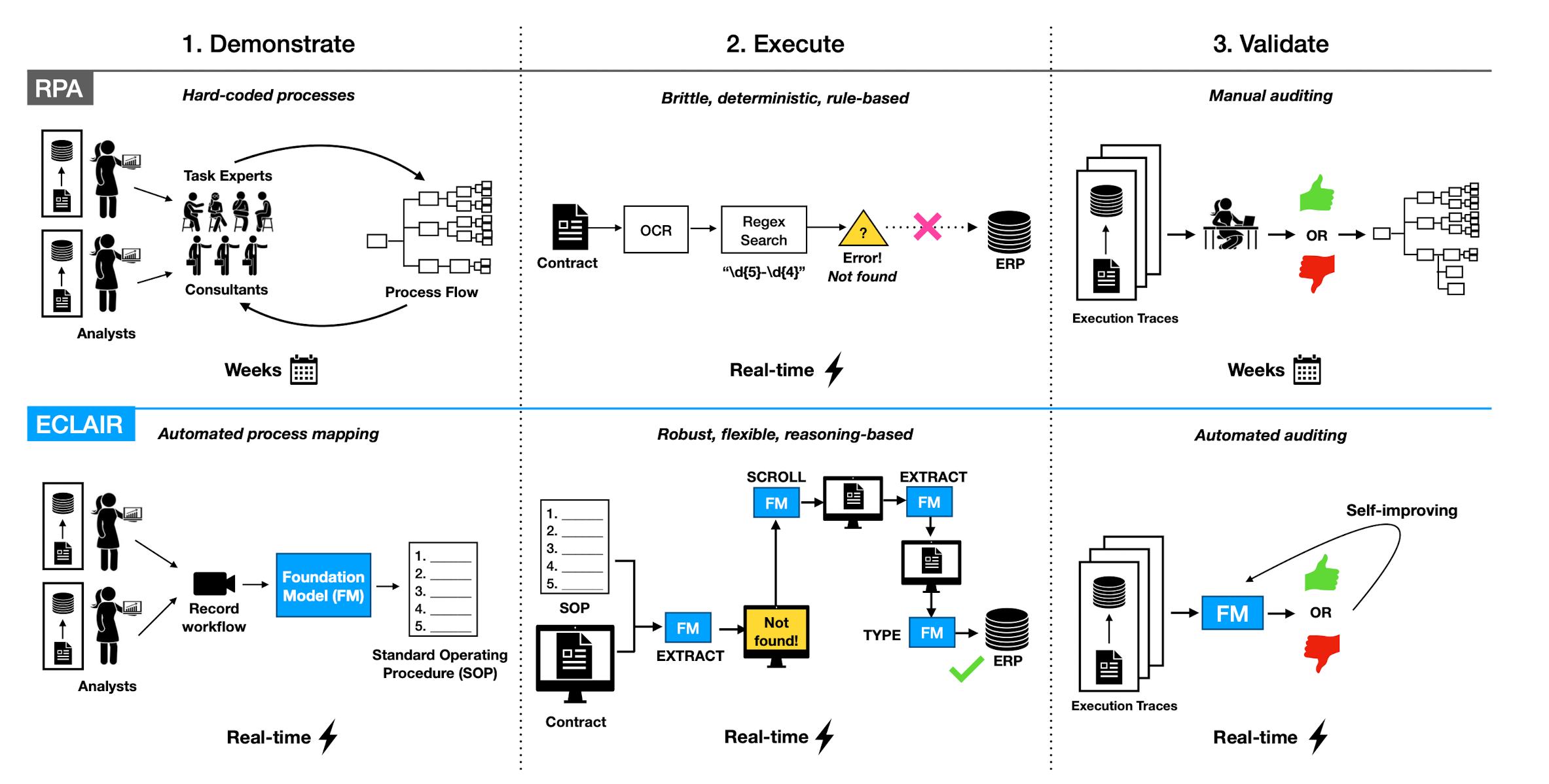

Automating the Enterprise with Foundational Models

Paper: ECLAIR

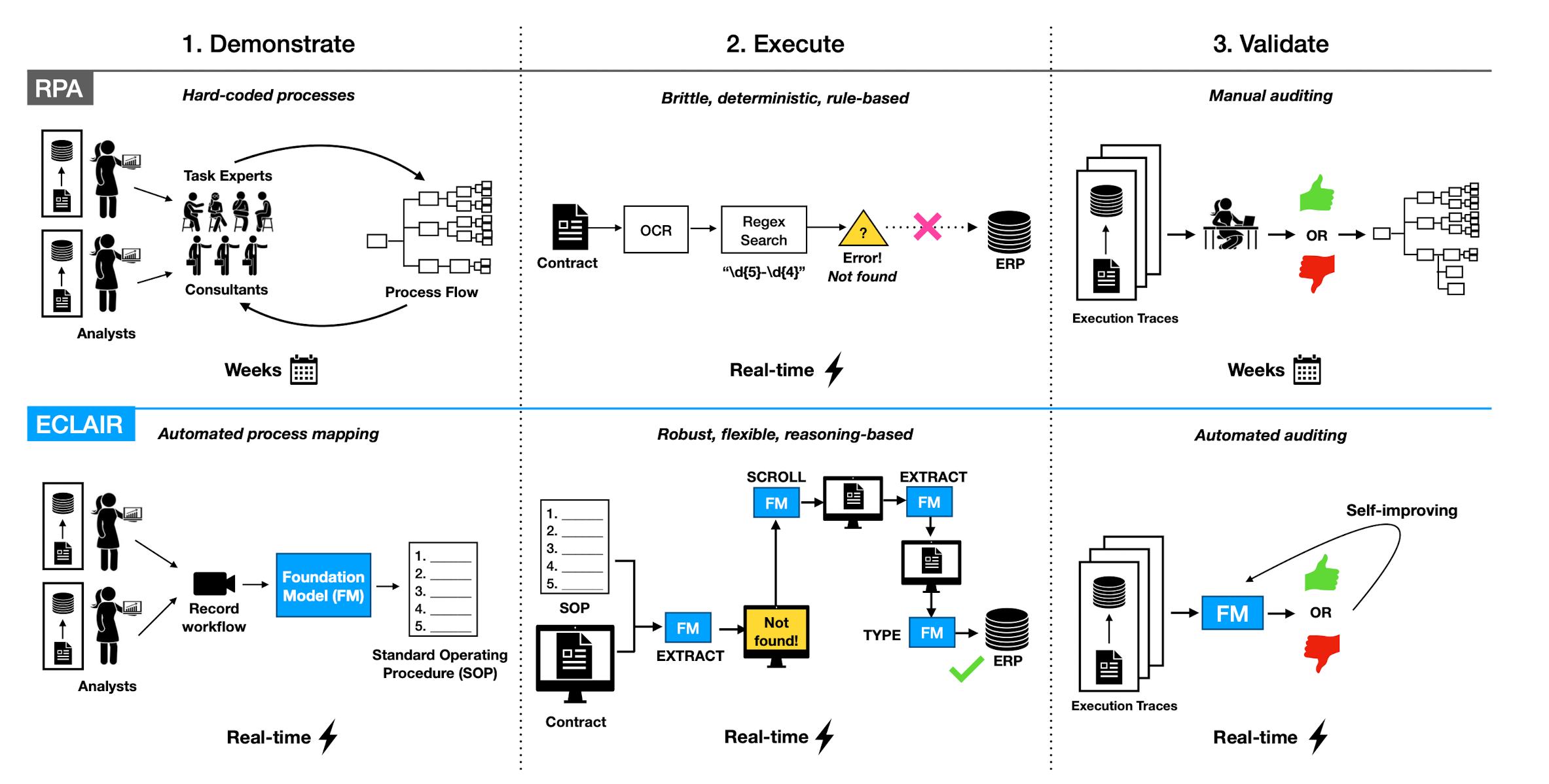

The paper tries to find automation strategies using LLMs for Robotic Process Automation type tasks in the enterprise.

The hypothesis is that if we are able to observe human interaction, find repeated patterns, encode those as SOP’s and then allow agent to run the same workflows we can unlock a tremendous value from enterprises.

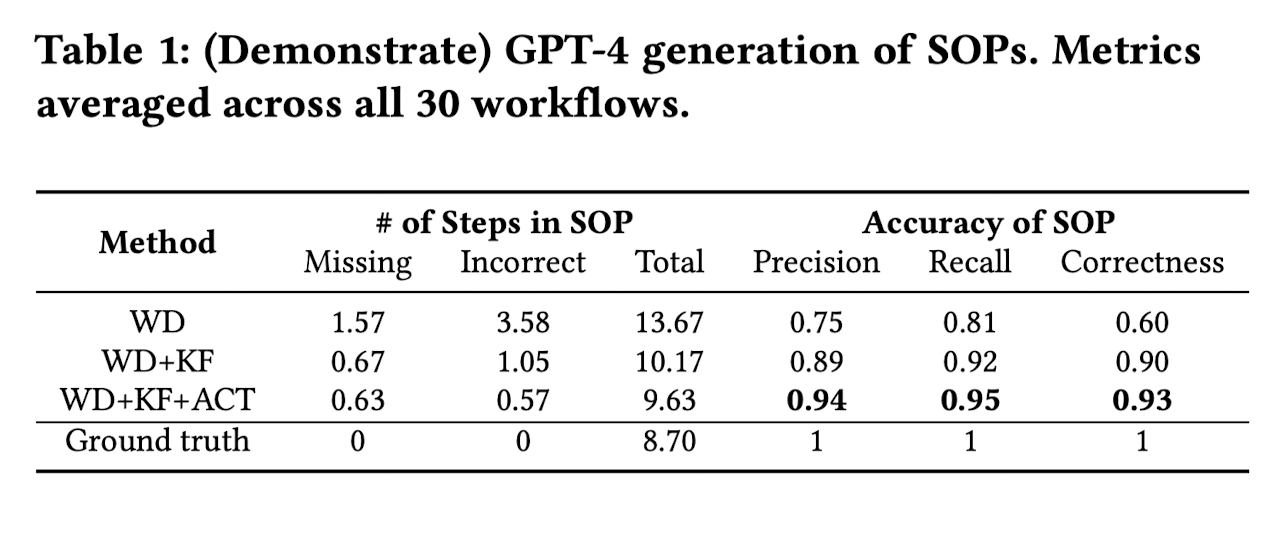

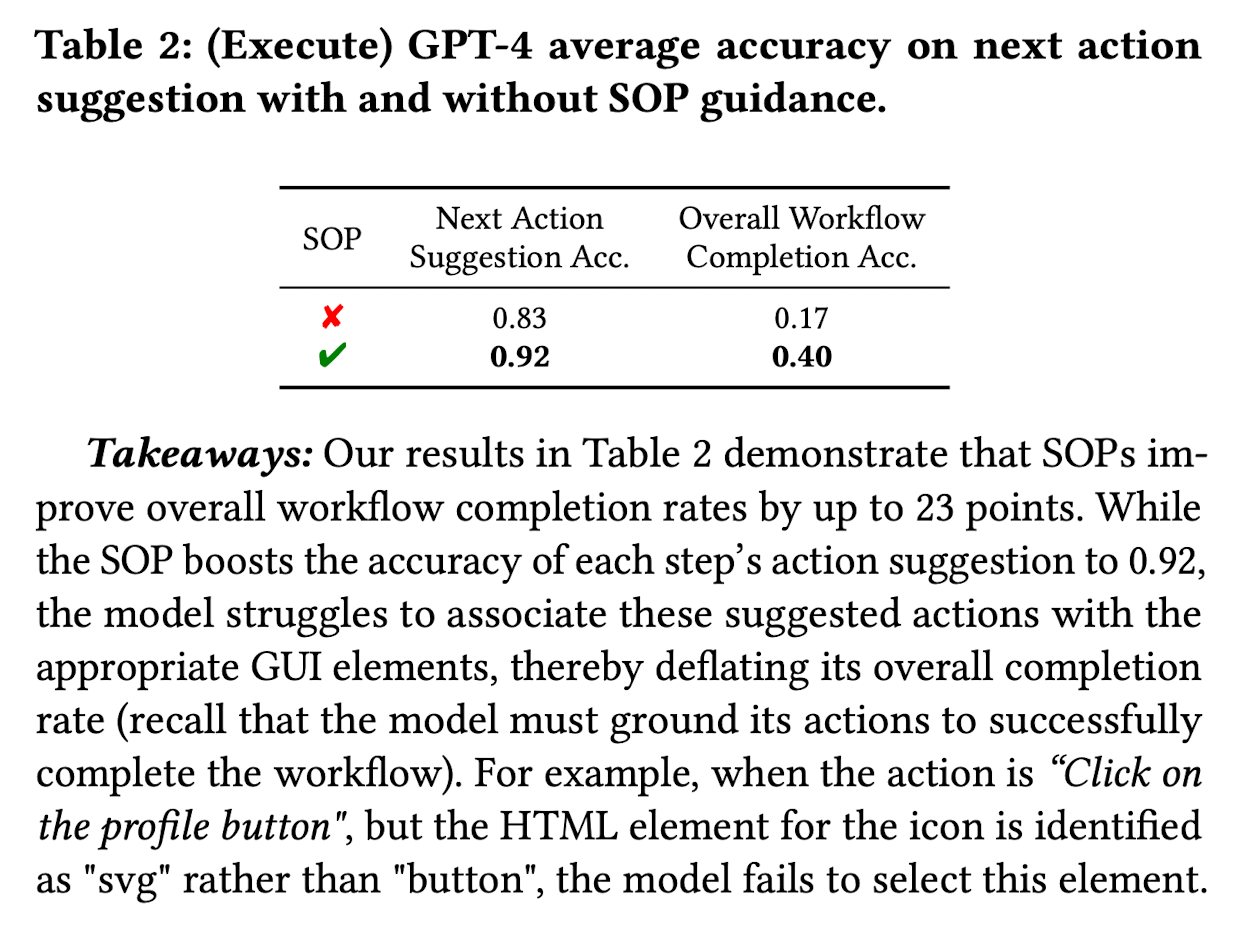

Demonstrate: ECLAIR uses multimodal FMs to learn from human workflow expertise by watching video demonstrations and reading written documentation. This lowers set-up costs and technical barriers to entry. Initial experiments show that ECLAIR can identify every step of a workflow based on screenshots from a demonstration with 93% accuracy. Execute: ECLAIR observes the state of the GUI and plans actions by leveraging the reasoning and visual understanding abilities of FMs [7, 53, 86]. Based solely on written documentation of a workflow, ECLAIR improves end-to-end completion rates over an existing GPT-4 baseline from 0% to 40% on a sample of 30 web navigation tasks [92]. However, this is still far from the accuracy needed for enterprise settings, and we identify opportunities to close this gap. Validate: ECLAIR utilizes FMs to self-monitor and error correct. This reduces the need for human oversight. When classifying whether a workflow was successfully completed, ECLAIR achieves a precision of 90% and recall of 84%.

What inputs work?

WD = Workflow Description

KF = Screenshots to show the UI state noted as Key Frames

ACT = Textual Action Log of click and keystroke

WD = Workflow Description

KF = Screenshots to show the UI state noted as Key Frames

ACT = Textual Action Log of click and keystroke

Results

TLDR; While this agentic emulation can detect the next action 92% of the time, the errors accumulate and the overall workflow completion is only 40%.

TLDR; While this agentic emulation can detect the next action 92% of the time, the errors accumulate and the overall workflow completion is only 40%.